- 23.05.2025

- News

Less smoke in apartment buildings, fewer hospital stays?

Since 2018, smoking has been banned in public housing across the United States—a rule introduced to protect the millions of residents often exposed to secondhand smoke from others. But has this measure really made a difference? A new study conducted in New York shows that the cardiovascular health of residents is beginning to improve.

Secondhand smoke—breathing other people’s smoke—remains a major cause of illness, especially among older adults. It can cause heart attacks, strokes, or worsen other health problems. In public housing, it is sometimes difficult to escape the smoke from neighbors, especially in older buildings with thin walls and shared ventilation systems.

Since July 30, 2018, all Public Housing Authorities (PHAs) in the United States are required to implement “smoke-free” policies in accordance with a rule established by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). This rule was adopted by HUD in order to “improve indoor air quality in public housing, protect the health of residents, visitors, and PHA staff, reduce the risk of catastrophic fires, and lower overall maintenance costs.”

The rule applies to all apartments, indoor common areas (hallways, stairwells, laundry rooms, community centers, etc.) as well as administrative offices. Smoking is also prohibited within 25 feet (7.6 meters) around these buildings. This ban applies to residents, visitors, staff, and contractors. When buildings do not have outdoor areas that meet this distance, the site becomes entirely smoke-free. Local authorities may, if space allows, create designated smoking areas, provided they are located outside the prohibited zones and are accessible to people with reduced mobility.

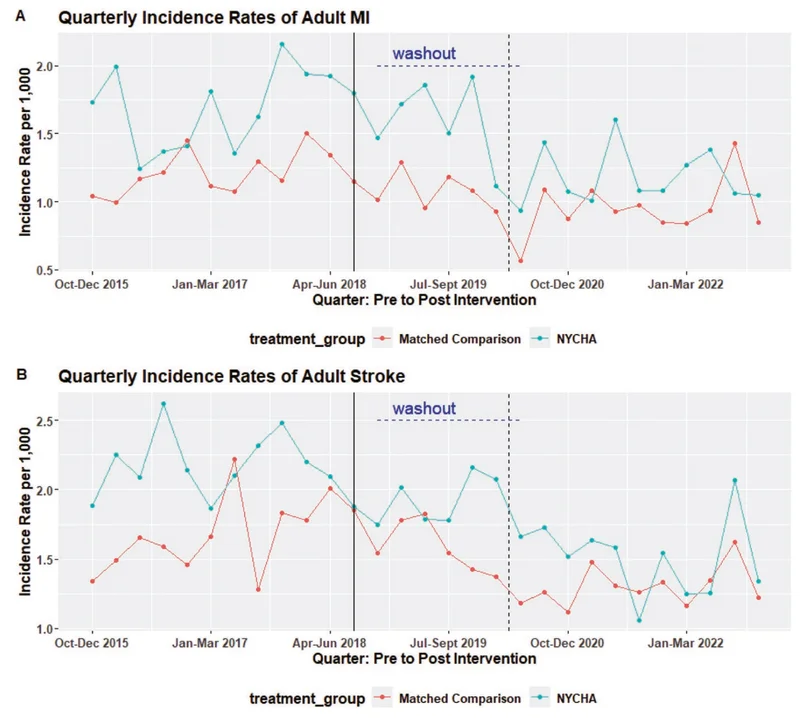

Nationwide, this rule applies to more than 700,000 housing units, more than 500,000 of which are occupied by older adults or by households including a younger person with a disability. At the time of its adoption, more than 600 PHAs had already implemented smoke-free policies in at least one of their buildings.To find out whether banning smoking inside buildings made a real difference, researcher Elle Anastasiou and her colleagues analyzed the medical data of more than 50,000 people aged 50 and older, living in buildings of the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), the largest public housing provider in the country. They compared these residents to other New Yorkers living in similarly low-income neighborhoods, but where the rule did not apply.The goal? To observe the trend in hospitalizations between 2015 and 2022 for heart attacks (myocardial infarctions) and strokes—conditions particularly sensitive to secondhand smoke. The trend shows a slight decrease in hospitalizations for these two cardiovascular events among social housing residents (see graph).

Modest but encouraging effects

The researchers note that these effects are modest, but they do exist. Most importantly, they appear gradually, which makes sense. It took time for the rule to be properly implemented: posters were installed, smoking cessation programs were launched, and managers received training to support tenants. It was from 2020 that the efforts became most visible. It would be interesting to repeat the study over time to measure the increasing impact of these measures.

An impact on a sensitive social context

One of the strengths of this study is that it focuses on a population often underrepresented in public health research: older adults living in public housing. These residents, often disproportionately exposed to secondhand smoke, may face multiple vulnerabilities: poverty, comorbidities, limited access to healthcare.The study thus supports the idea that public health policies integrated into housing can have structural effects on the health of the most vulnerable populations.This type of policy could inspire other cities, other countries, and be extended to other shared living environments, such as student residences or senior homes. Of course, this must be accompanied by support: help with smoking cessation, mediation between neighbors, or social assistance.