How the tobacco industry is trying to avoid a ban on filters

Defenders of tobacco company interests have so far remained discreet during the plastics treaty negotiations. But they exert a more diffuse influence on national delegations, much like the one representing Switzerland.

Of the 1,900 delegates who attended the latest round of negotiations on the plastics treaty, two- thirds were state representatives and one-third were non-governmental actors. “Among the latter, we find both environmental organisations or organisations defending the interests of citizens, as well as those representing business interests, including representatives of tobacco companies,” underlines Chris Bostic, public policy director for Action on Smoking and Health (ASH), who attended the negotiation sessions.

Danielle van Kalmthout, general coordinator at the Belgian Alliance for a Smoke-Free Society, who took part in the last two sessions, was aware of only one lobbyist defending the interests of the tobacco industry during the November 2023 Kenyan discussions. “The chemical and fossil fuel sectors were much better represented,” she emphasizes.

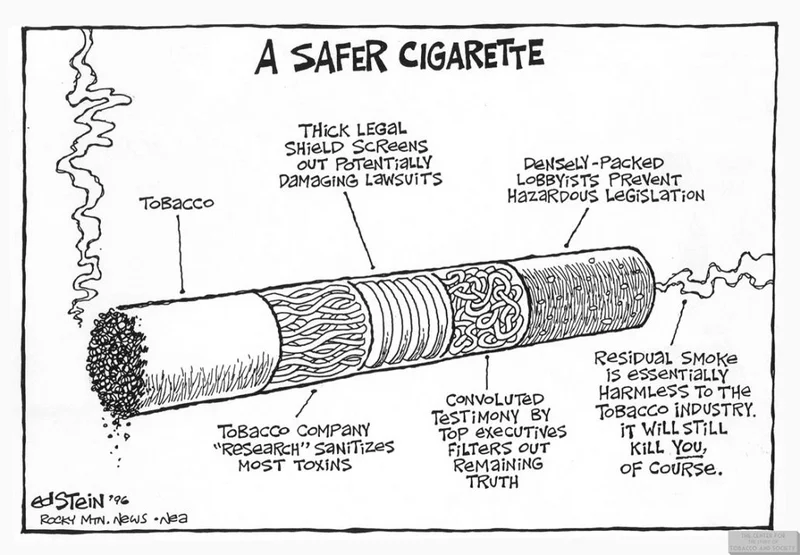

When seeking to influence the outcome of a debate, however, tobacco companies have mastered the art of dissimulation. “They often intervene through organisations whose interests are aligned with theirs, such as national chambers of commerce,” says Debbie Sy, in charge of strategic affairs for the Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control.

They also seek to influence the position of members of state delegations ahead of negotiations. “The real lobbying efforts take place on the sidelines of official discussions anyway, in the corridors or during coffee breaks,” adds Chris Bostic. “They also sometimes stay in a five-star hotel and invite delegates there for dinner in the evening.”

Thomas Novotny, a public health and environmental specialist at the University of San Diego (US), who focuses his research on tobacco, also points out that the companies first affected by a ban on cigarette filters are the filter manufacturers, namely groups like Eastman Chemical Company, Celanese, or Dow Chemical. “We should expect to see them intervene during the next rounds of negotiations,” he said.

Nothing prevents them from participating in discussions. Unlike public health policy negotiations, from which tobacco companies are excluded under Article 5.3 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, no similar provision exists for environmental treaties like the one on plastics.[1]

However, a resolution from the United Nations Economic and Social Council dating from 2017 directs UN agencies to prevent interference from the tobacco industry.[2] The United Nations Global Compact, the World Health Organization, the United Nations Development Program, and the World Bank have for their part excluded tobacco company representatives from their forums.[3]

Asked about tobacco industry participation in the plastics treaty negotiations, Switzerland’s Rebekka Reichlin, spokesperson for the Federal Department of the Environment, recalls that the United Nations’ General Assembly resolution that gave birth to the treaty "underlines the importance and the necessity" that the discussions be open not only to UN member states, UN agencies, and regional economic integration organisations, but also "to the parties’ interested stakeholders”. More precisely: “The treaty must be drafted on a solid knowledge base, which implies the participation of stakeholders who have been accredited for these discussions”.

Tobacco companies will likely deploy arguments on the health benefits of filters and the possibility of developing recyclable or biodegradable filters. When the Superior Health Council in Belgium recommended banning filters in April 2023, British American Tobacco Benelux immediately reacted by deeming the proposal “unrealistic, ineffective, and counterproductive”.

Philip Morris, for its part, estimated that this would represent a distortion of the single European market and would encourage illicit trafficking of filtered cigarettes. Cimabel, which represents tobacco companies present in Belgium and Luxembourg, declared that “studies have shown that an absence of filters can lead to an increase in toxins inhaled by consumers”.[4]

During the first two rounds of plastics treaty negotiations, “the issue of cigarette filters was only marginally addressed by national delegations,” says Danielle van Kalmthout. Significant background education work had to be done with delegates. “The pollution caused by filters is poorly understood and they are still seen as a risk reduction tool,” she notes. Many delegates nevertheless showed openness regarding a ban on cigarette filters.

The turning point came during the third round of negotiations. The World Health Organization and the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control secretariat issued a position statement calling for an immediate ban on plastics in tobacco products, including packaging and e-cigarettes, leaving the door open to gradual elimination where a ban would be unfeasible. A handful of countries, particularly in Latin America, have also publicly supported such a position, adds Danielle van Kalmthout.

Even more significantly, the conclusions of one of the contact groups responsible for developing the first draft of the treaty, published in November 2023, mention cigarette filters as an example of plastics that should be on a list of prohibited products in the treaty annex. “This is the only product mentioned by name,” she explains. The criteria for inclusion on this list could be the non-essential nature of the object, its toxicity, its non-recyclability, its propensity to be littered into the environment, and its lack of biodegradability.

Ms van Kalmthout believes that the presence of tobacco company representatives will strengthen as the discussions progress and positions take focus. “The intervention of the World Health Organization and the mention of cigarette filters in the first draft of the treaty will have had the effect of an electric shock,” she thinks. This will motivate them to intervene more markedly.”

As for the Confederation, we are not closing the door to a ban on cigarette filters. “Switzerland is committed to reducing plastics production, to abandoning non-recyclable plastics that contain problematic additives, as well as to eliminating problematic and avoidable plastics such as unnecessary packaging and certain single-use plastics,” indicates Rebekka Reichlin.

She recalls that the first draft of the treaty “explicitly aims to ban short-lived plastics and intentionally added microplastics, which could include plastic cigarette filters, as long as they are included in a future annex agreement".

In its response to an inquiry filed at the end of 2023 by Vaud Green Party national councilor Léonore Porchet, the Federal Council was, however, more hostile. “To justify the ban on cigarette filters, it would be necessary to unequivocally demonstrate their harmfulness to the environment,” they said. Furthermore, such a ban would constitute a severe attack on the freedom of trade and industry. This is why the Federal Council is currently relying on voluntary economic measures.”[5]

Bern has, however, joined the High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, a collection of countries led by Norway and Rwanda that has set the goal of ending plastic pollution by 2040. At the Davos summit in January 2023, Alain Berset, then-President of the Confederation, even expressed his wish to host the secretariat of this multi-state body on Swiss soil. Chris Bostic, however, denounces the “dilution” of this coalition as it is joined by countries like Switzerland, which are more interested in a weak treaty.

Anti-tobacco circles believe that the Swiss delegation, made up of four people from the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN), is more in favour of the arguments of the tobacco industry than those of environment advocates. “At least one of its participants also attended a series of round tables devoted to cigarette butt littering into the environment with representatives of tobacco companies,” underlines Kris Schürch, who co-wrote the Swiss section of the report, “Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index.”

Albert Rösti, head of the Federal Department of the Environment, Transport, Energy, and Communications, and a member of the Swiss People’s Party, is also not known for his pro-environmental positions. “There was a clear change of direction upon his arrival at the head of the department”, which houses the FOEN, confirms Delphine Klopfenstein Broggini, a Green Party national councilor from Geneva.

See you in April 2024 in Ottawa, Canada, for the continuation of the deliberations…

[2] https://ggtc.world/library/tobaccos-toxic-plastics-a-global-outlook

[3] https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1282655/full

[4] https://www.parlament.ch/fr/ratsbetrieb/suche-curia-vista/geschaeft?AffairId=20234458