Changes in use over the past 30 years

- Smoking increased noticeably during the 1990s, then decreased during the 2000s. Afterward it stabilised at what is considered a high level and has changed only slightly in the past 10 years.

Several different studies help us to get a feel for the changes in smoking behaviour in Switzerland. Nevertheless, only one study is still actively monitoring the adult population – the Swiss health survey (Enquête suisse sur la santé - ESS). Since its inception in 1992, the ESS’s main limitation is that it is conducted only once every five years, which makes it impossible to get a continuous reading of the evolution of smoking in our country. Another limitation relating to the long time period between measurements is the impossibility of determining whether the differences between any two points in time represent real changes or only the result of temporary variations – for example, influences of the specific context of a given year. Thus, the tendencies in the changes in rates of smoking, apart from the period 2001 to 2016 – when the Monitorage sur le tabac Suisse (TMS[1]) and the Monitorage Suisse des addictions (AMIS[2]) were being conducted – must be interpreted cautiously.

Tendencies since the 1990s

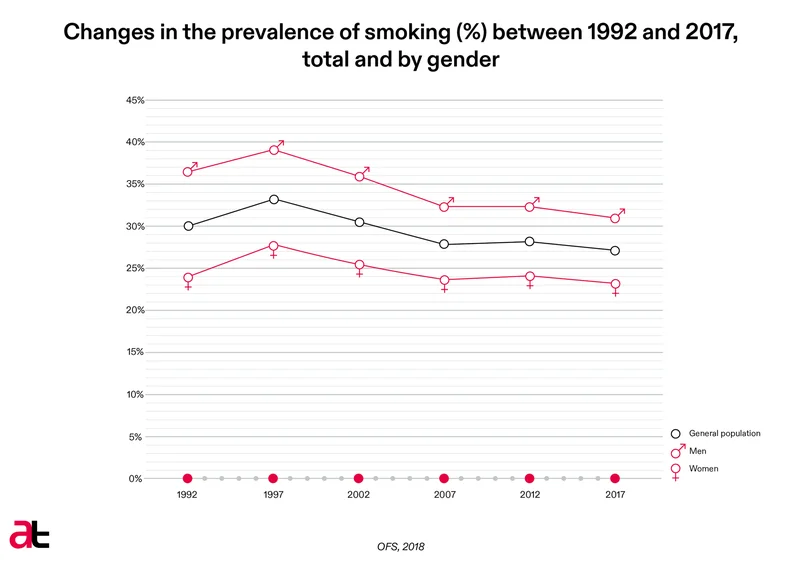

The Swiss health survey has followed the changes in tobacco consumption in the 15-and-over population since 1992. While an increase in the prevalence of smoking was observed between 1992 and 1997, this was followed by a decrease between 1997 and 2012 (Figure A1A-4). Since 2012, the proportion of smokers appears to have stabilised (around 27%). These general tendencies have been observed for men and women alike. It should also be noted that the difference in prevalence between men and women has diminished noticeably since 1992.

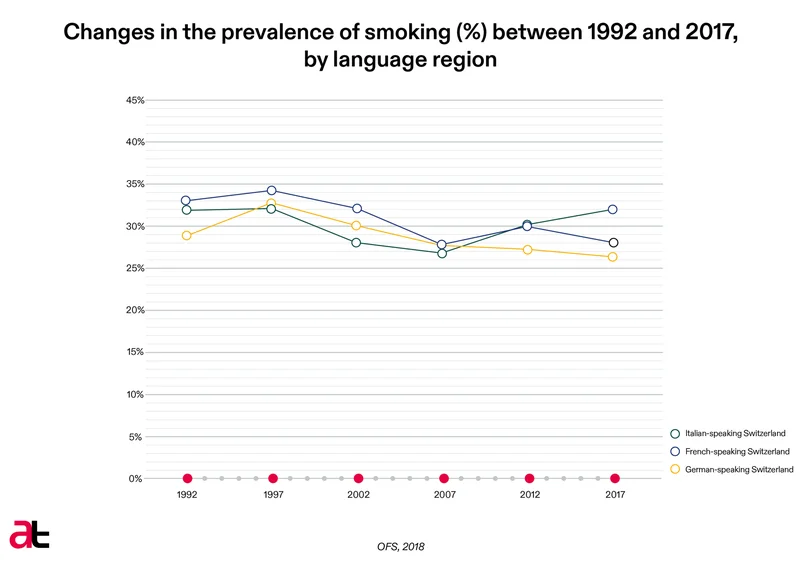

Figure A1A-4 – Changes in the prevalence of smoking (%) between 1992 and 2017, total, and by sex and language region, HBSC 1992-2017 (Sources OFS, 2018[3])

Different tendencies in the evolution of use among language regions (Figure A1A-4) and among age groups (Figure A1A-5) were observed, however, during this period. For example, in Italian-speaking Switzerland, while the pattern of use seemed to follow that of the rest of the country up until 2007, the proportion of smokers appeared to increase after that year, whereas in German-speaking Switzerland, smoking declined and then stabilised, and in French-speaking areas it rose slightly in 2012 and then returned to its 2007 level in 2017.

Figure A1A-5 – Changes in the prevalence of smoking (%) between 1992 and 2017, total and by age group, HBSC 1992-2017 (OFS, 2018[4]).

Changes since the early 2020s

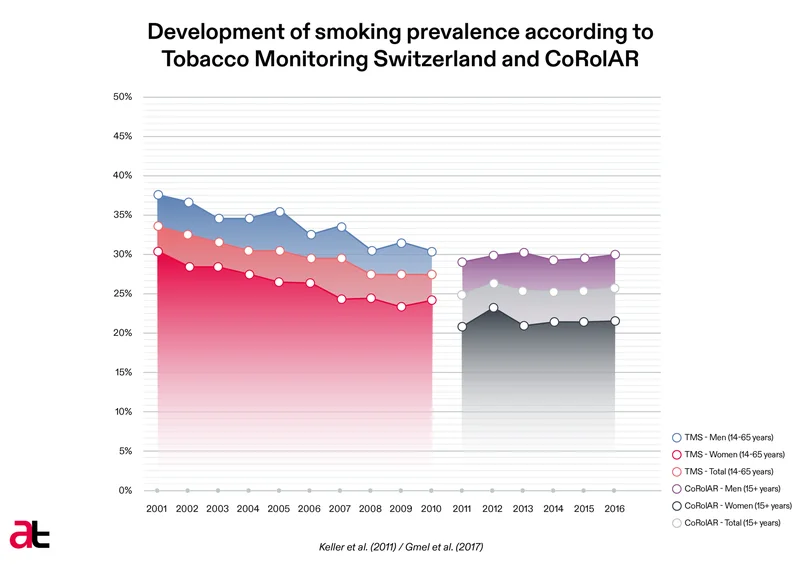

During the period from 2001 to 2016, two studies monitoring tobacco use followed one another: the Monitorage sur le tabac Suisse (TMS), from 2001 to 2010, and the Continuous Rolling Survey of Addictive Behaviours and Related Risks (CoRolAR) from the Monitorage suisse des addiction, conducted between 2011 and 2016.

The reporting methods of the TMS and the CoRolAR were similar in some ways, such that it is possible to compare the prevalence reported in the two studies, but it must be done with some reservations (particularly because the population of reference was slightly different; the TMS addressed the population ages 14 to 65, while the CoRolAR targeted 15-year-olds and up).

Keeping in mind these considerations, these studies suggest, on the one hand, a regular and continuous decline in the prevalence of smoking from 2001 to 2008 – sliding from 33% to 27% of smokers – followed by a long phase of stagnation with slight variations (Figure A1A-4; note that the differences between 2010 and 2011 are partly due to a change in the methodology of the study (Kuendig et al., 2012[5]).

Figure A1A-6 – Changes in the prevalence of smoking (%) based on the Monitorage sur le tabac Suisse 2001-2010 and the CoRolAR 2011-2016 studies (Sources Keller et al., 2011[6] and Gmel et al., 2017[7]).

The decline observed from 2001 to 2008 in the TMS appears to be mainly linked to a decrease in daily smoking (decline from 24% to 19% for the population as a whole), while the proportion of occasional smokers stayed relatively stable over the whole of the period covered by the TMS (2001 to 2010; Keller et al., 2011[8]). The downward trend in smoking in Switzerland as a whole for the period up to 2008 can also be observed for the different language regions of the country (the decline being, however, slightly smaller in Italian-speaking Switzerland than elsewhere).

Cross-analyses based on available data sources

With a goal of analysing long-term trends in tobacco and alcohol use, an analysis published in 2018 (Gmel et al., 2018[9]) looked at different sources of data conjointly: the quadrennial Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), conducted for 11 to 15-year-old students since 1986, the ESS, and the CoRolAR study from the Monitorage suisse des addictions.

Remembering that using and interpreting data from several studies presents both advantages and disadvantages, the authors base their analyses not on “exact” prevalence rates, but on the direction of the changes shown (increase or decrease). The observations made when combining the different existing sources of data reinforce, in the end, those that appeared separately in each of the studies: smoking appears to have risen slightly among the Swiss population during the 1990s; it seems to have declined afterward and stabilised more or less at its current level in the latter part of the 2000s.

Based on the studies examined, the evolution of tobacco consumption in Switzerland over time, between 1992 and 2016, or as a function of age, between the ages of 15 and 89, reflect overall what is described in the international literature as a “smoking epidemic”[10] [11](or “épidémie de tabagisme”). That is, men’s smoking began earlier, and progressed more rapidly than for women. After having reached an earlier peak, the decline in the prevalence in smoking was also earlier for men than for women. According to this theory, women follow the trend for men 10 to 30 year later, whether in the progression phase of smoking or in the subsequent stabilisation and decline stages.

[1] http://www.tabakmonitoring.ch/index.html; zuletzt besucht am 9.12.2021.

[2] https://www.suchtmonitoring.ch/de/page/8.html; zuletzt besucht am 9.12.2021.

[3] https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/sante/determinants/tabac.assetdetail.6466022.html; zuletzt besucht am 9.12.2021.

[4] https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/statistiques/sante/determinants/tabac.assetdetail.6466022.html; accédé le 9.12.2021.

[5] Kuendig, Hervé; Georges, Aurélien; Notari, Luca (2012): Comparaison de résultats du Monitorage sur le Tabac Suisse 2010 et de l’enquête CoRolAR 2011. Sucht Schweiz. Lausanne. Download.

[6] Keller, Roger; Radtke, Theda; Krebs, Hans; Hornung, Rainer (2011): Der Tabakkonsum der Schweizer Wohnbevölkerung in den Jahren 2001 bis 2010. Tabakmonitoring - Schweizerische Umfrage zum Tabakkonsum. Download.

[7] Gmel, Gerhard; Kuendig, Hervé; Notari, Luca; Gmel, Christiane (2017): Monitorage suisse des addictions Consommation d’alcool, de tabac et de drogues illégales en Suisse en 2016. Sucht Schweiz. Lausanne. Download.

[8] Keller, Roger; Radtke, Theda; Krebs, Hans; Hornung, Rainer (2011): Der Tabakkonsum der Schweizer Wohnbevölkerung in den Jahren 2001 bis 2010. Tabakmonitoring - Schweizerische Umfrage zum Tabakkonsum. Download.

[9] Gmel, Gerhard; Notari, Luca; Gmel, Christiane. (2018): Rauchen und Alkoholkonsum in der Schweiz: Trends übber 25 Jahre, Kohorteneffekte und aktuelle Details in Ein-Jahres-Altersschritten – eine Analyse verschiedener Surveys. Sucht Schweiz. Lausanne. Download.

[10] Lopez, Alan D; Collishaw, Neil E; Piha Tapani. A descriptive model of the cigarette epidemic in developed countries. Tob Control. 1994;3:242–7.

[11] Thun, Michael; Peto, Richard; Boreham, Jillian; Lopez, Alan D. Stages of the cigarette epidemic on entering its second century. Tob Control. 2012;21:96–101.

AT Switzerland, September 2022